Meet the Market Makers: The ETF Ecosystem in Action

In my last article, we introduced you the WHO of the ETF ecosystem. We’ve defined the different types of market makers (MMS) and other market participants, and explained the role each plays in day-to-day ETF trading. Today we are going to discuss Why these players are part of the ETF ecosystem – how their business models differ and what motivation they each have for trading ETFs.

Why is this important? Simply put, the interaction between these different market participants can generate liquidity for the investing public. Moreover, any of recent discussions around regulatory changes for market makers – for example, their obligations in the market – must start with the strategies employed by these companies. This understanding can also help dispel fears about a potential trading breakdown leading to illiquid ETF securities markets.

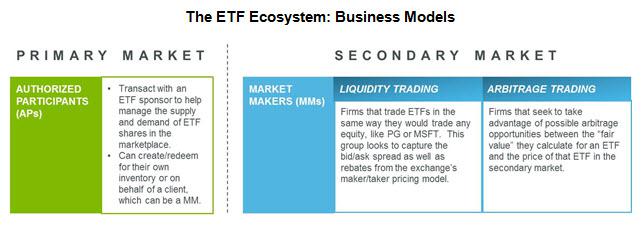

Among the many market players, there are 2 main categories that facilitate day-to-day ETF trading: Authorized Participants and Market Makers. The visual below explains how everyone regularly interacts with ETFs.

Authorized Participants (AP)

On the Primary market side, Authorized participants provide a service by dealing with an ETF sponsor to manage the supply and demand for ETF shares in the market. Some access points create and redeem new stocks to manage their own inventory, while those who do not engage in market making simply facilitate creations and redemptions on behalf of their clients (which may include market makers). Even the concept of “creating to lend” – creating new actions in order to lend them to a short seller – is just another example of customer facilitation.

Market makers

What incentive do market makers have to make double-sided markets – and therefore providing liquidity – in ETFs? We see two different business models in the MM space.

The first are companies looking to take advantage of possible arbitrage opportunities between their own calculated “fair value†and the price of the ETF on the secondary market. Arbitrage refers to the simultaneous buying and selling of an asset in order to profit from a difference in the price.

If, for example, the secondary market price of an ETF is higher than the fair value that an MM has calculated for that ETF, the MM will sell the ETF, buy a correlated security as a hedge, such as the underlying basket securities, then use an AP to create the ETF to cover their short position. As we discussed earlier, the market maker and the AP could be the same company. Often these price gaps are quite small and can disappear almost instantly. In fact, one of the main reasons why ETFs generally trade so close to their underlying value is the number of companies that use this type of strategy.

Now, estimating the fair value of an ETF is not an exact science – especially for US-listed ETFs with international underlying securities, as overseas markets can be closed when US markets are open. These companies take a risk when they use an arbitrage strategy. MMs calculate this value based on a number of factors – it can be as simple as pricing the ETF from the underlying basket or as complicated as adjusting via the performance of correlated securities.

The second MM business model we see are companies that trade ETFs the same way they trade stocks, like PG or MSFT. This group seeks to capture the bid/ask spread as well as discounts from the exchange’s maker/taker pricing model. the bid/ask spread is pretty self-explanatory – if MMs can buy on the bid and sell on the bid, they will make up the difference after the associated transaction fees. The maker/taker pricing model is where exchanges pay rebates to those who provide liquidity and charge fees to those who take liquidity. If a market making firm can generate more cash than it takes in, it will receive more rebates from the exchange than it pays in fees. This type of activity is more common in highly liquid ETFs.

_______________________________________________________________________

As you can see, each market player in the ETF trading ecosystem has a different business model when it comes to ETF trading, and all of them interact to provide the liquid markets the public expects.

Trading volume is the primary driver of success for any of the above market making models. But what about new and less liquid products that have low trading volume? We’ll conclude this series with a discussion of why this is a problem and what exchanges are doing to address it.

Although market makers generally profit from differences between the net asset value and the share price of the iShares Fund through arbitrage opportunities, there is no guarantee that they will. With short selling, an investor faces the potential for unlimited losses as the price of the security rises.The strategies discussed are strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell, or an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. There is no guarantee that the strategies discussed will be effective.

Disclosure: I have no positions in the stocks mentioned and do not plan to initiate any positions in the next 72 hours. I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I do not receive any compensation for this. I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

Comments are closed.